The Enlhet in Paraguay

For more than twenty years, the Enlhet Institute Nengvaanemkeskama Nempayvaam Enlhet (Growing Our Language and Knowledge) has devoted its work to assisting the Enlhet people to look at themselves and to reflect on their identity and history. This work is necessary because the colonization of their land over the last hundred years has created the impression that the Enlhet are not capable of living independently in the modern world. We, Ernesto Unruh and Hannes Kalisch, have collected the accounts of Enlhet elders, of men and women who have witnessed how their society has lost its independence and land and thus the basis of its life. These narrators are no longer alive. However, in the coming years we would like to make their oral accounts, which are only available in Enlhet, accessible to their descendants.

The Enlhet. History. The Enlhet (formerly known as Northern Lengua) are the largest group in the Enlhet-Enenlhet (also Maskoy) language family in the Paraguayan Chaco, numbering 8,200 people. Until about 1930, they lived in small groups in an area of some 20,000 square kilometres. Starting from a main site, each small group moved cyclically within their home area, following the ripening of different fruits, the appearance of wildlife and the seasonal state of their waterholes.

On the one hand, the Enlhet emphasised the organization of living together in equilibrium, which they refer to as nengelaasekhammalhkoo, “to be well-disposed towards each other; to take each other seriously.” On the other, building elaborate infrastructure in their land or creating and increasing material wealth was not a goal for the Enlhet.

Therefore, when German-speaking Mennonite groups immigrated to Enlhet territory from 1927 onwards, the newcomers thought they had come to an empty land and claimed it for themselves without question. Soon after, the Enlhet had to cope with an increasing loss of their livelihood. A self-determined life became increasingly difficult for them.

Almost simultaneously with the arrival of the settlers, the dispute between Paraguay and Bolivia over ownership of the Chaco escalated in the centre of Enlhet territory, and when war broke out between the two countries in 1932, the Enlhet were directly exposed to its violence. In the same year, there was a smallpox epidemic among the Enlhet, which killed at least half of the population in just a few months. Against the backdrop of these traumatic experiences, the intensive missionary efforts of the immigrants quickly met with success: towards the end of the 1950s, almost all Enlhet accepted Christian baptism within the space of a few years, and they were settled in so-called mission stations, in reservations. This reduction to the mission stations sealed the loss of their land and their way of life.

Almost simultaneously with the arrival of the settlers, the dispute between Paraguay and Bolivia over ownership of the Chaco escalated in the centre of Enlhet territory, and when war broke out between the two countries in 1932, the Enlhet were directly exposed to its violence. In the same year, there was a smallpox epidemic among the Enlhet, which killed at least half of the population in just a few months. Against the backdrop of these traumatic experiences, the intensive missionary efforts of the immigrants quickly met with success: towards the end of the 1950s, almost all Enlhet accepted Christian baptism within the space of a few years, and they were settled in so-called mission stations, in reservations. This reduction to the mission stations sealed the loss of their land and their way of life.

The Enlhet. Present. Today these mission stations are called comunidades (communities). They nevertheless remain organisationally modelled on the Mennonite social model and are administered by a Mennonite “counsellor” who lives in the respective comunidad. The Christian Mennonite church serves as the institution that determines social life. These circumstances lead the Enlhet to a strong orientation towards external proposals and models that have no counterpart in their own history and tradition. At the same time, however, their daily lives remain variously linked to traditional ways of perceiving, arguing or evaluating, and thus motivate their actions considerably. A contradiction has arisen between a concrete way of life connected to their own tradition and forms of argumentation oriented towards the system of thought of the immigrants who now have the say in the land of the Enlhet. Weighed by this contradiction, Enlhet society has neglected, even suppressed, conversation about all that is inherent in its own historical path and tradition. Bubbles of silence have emerged. These silent spaces stand in the way of the continuation and transformation of potentials for action that are visible in everyday life. This has a paralyzing effect.

The accounts of the elders.  The present of Enlhet society is characterized by life in comunidades, where the people live in a very restricted space as poor agricultural labourers. Access to other ways of life is structurally denied to them; other ways of life are often no longer even imaginable. In contrast, the elders – witnesses of change –, describe multiple possibilities for action when they share details of their lives. Their accounts show a diversified life in a world that they shaped autonomously and that fulfilled their material needs satisfactorily. They reflect great freedom. These accounts thus stand in marked contrast to the present and create a tension that encourages them to imagine a different future and therefore also to engage with the present in a new way.

The present of Enlhet society is characterized by life in comunidades, where the people live in a very restricted space as poor agricultural labourers. Access to other ways of life is structurally denied to them; other ways of life are often no longer even imaginable. In contrast, the elders – witnesses of change –, describe multiple possibilities for action when they share details of their lives. Their accounts show a diversified life in a world that they shaped autonomously and that fulfilled their material needs satisfactorily. They reflect great freedom. These accounts thus stand in marked contrast to the present and create a tension that encourages them to imagine a different future and therefore also to engage with the present in a new way.

Over the past twenty years, we have regularly visited Enlhet elders, men and women, and over the course of several years the individual narrators have intensively recounted their experiences and memories. This has resulted in more than 700 hours of recordings in Enlhet with authentic reflections on their history and lives. We have also made trips through Enlhet lands with the elders, recording their knowledge of the original toponymy and registering the places using GPS.

These witnesses of change have since died. However, many of their accounts of the history and traditions of their people have been preserved in our audio and audiovisual recordings.

Results of our work. We have continuously made selections from these recordings accessible as audio publications and videos and distributed them via radio broadcasts, DVDs and online. With the collected GPS data we have produced maps showing the original and present geography. These maps have been put up as signs in public places. With our publications, which are very present in the Enlhet community, an awareness has grown that a conversation about one’s own history is legitimate and necessary. The basis of shared knowledge about one’s own people and their history has been refreshed; this knowledge was in danger of being forgotten because it was no longer passed on. We have observed that the interest in the accounts among the Enlhet increases the more time passes since the death of the narrators. Also, as high quality literary representations, our publications form an important link in the efforts to preserve and strengthen Enlhet as a language. Moreover, for Enlhet schools our publications represent almost the only materials that include Enlhet language and life.

We have continuously made selections from these recordings accessible as audio publications and videos and distributed them via radio broadcasts, DVDs and online. With the collected GPS data we have produced maps showing the original and present geography. These maps have been put up as signs in public places. With our publications, which are very present in the Enlhet community, an awareness has grown that a conversation about one’s own history is legitimate and necessary. The basis of shared knowledge about one’s own people and their history has been refreshed; this knowledge was in danger of being forgotten because it was no longer passed on. We have observed that the interest in the accounts among the Enlhet increases the more time passes since the death of the narrators. Also, as high quality literary representations, our publications form an important link in the efforts to preserve and strengthen Enlhet as a language. Moreover, for Enlhet schools our publications represent almost the only materials that include Enlhet language and life.

The key focus of our work lies in strengthening the communication processes within Enlhet society. Beyond this goal, we have produced a variety of publications on the subject of Enlhet language and life (mostly in Spanish, but also in German and English). Our particular concern lies with the European settlement of the Chaco, which has turned the indigenous peoples into little-respected foreigners in their own land. We examine the reasons, the course and the consequences of the indigenous peoples’ dwindling possibilities for protagonism and the capacity to act, in order to identify possible ways in which they can regain their agency. From the perspective of the Enlhet and in the light of their history, we reflect on possible forms of coexistence in the Chaco that leave a space for all population groups and grant them their own possibilities for agency.

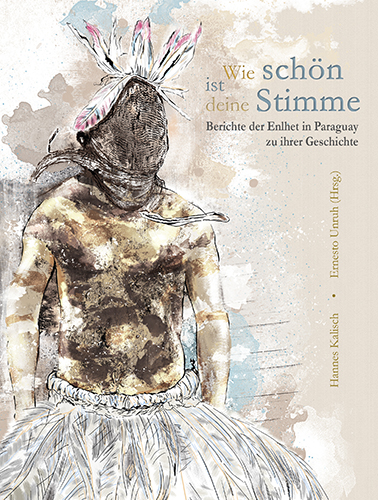

Over the years we have also published various essays and anthologies in non-indigenous languages to bring awareness of the Enlhet experience to a wider public. Among others, we contributed a chapter to the Palgrave International Handbook of Peace Studies (“Nengelaasekhammalhkoo: An Enlhet Perspective”) published in English in 2011. An anthology of Enlhet accounts (Wie schön ist deine Stimme) was published in German in 2014, as well as in Spanish in 2020 (¡Que hermosa es tu voz!). In 2021, we published a reflection about Enlhet territoriality based on the accounts of Maangvayaam’ay’ with Florida University Press. This essay is titled “‘They Only Know the Public Roads.’ Enlhet Territoriality during the Colonization of Their Lands,” and forms a chapter in Re-imagining the Gran Chaco: Identities, Politics, and the Environment in South America, edited by Hirsch, Canova y Bioccia. In March 2022, McGill-Queen’s University Press in Canada is to publish Don’t Cry. The Enlhet History of the Chaco War, the English translation of ¡No llores! (2018), a collection of Enlhet accounts of the Chaco War period (1932-1935).

Further work. The audio and audiovisual publications allow easy and quick access to the content the eyewitnesses share. This is important because the Enlhet read little. A written elaboration of the accounts nevertheless has its merits. When the narrators repeated their accounts, they never did so the same way. As a result, a large amount of information was gathered that is not fully reflected in a single version. The written version allows us to weave the variations into each other and thereby significantly increase the detail of the edited accounts. In doing so, we are careful to remain faithful to the intentions of the narrators and not to distort the content of their testimonies. We plan to publish the accounts of 30 narrators, men and women, as separate books for each of them in Enlhet over the next few years (corresponding examples already exist in the Toba-Enenlhet and Guaná languages).

The recordings must first be transcribed, followed by combining the variations on the same theme into one text. In a language without a written tradition, techniques for representation have to be developed that do justice to both the specific language and the content of the reports. We have worked continuously on the transcription of our recordings over the last two decades. This part of the work is now almost complete. Some of the accounts have already been compiled into a coherent text; for others this step is still pending. In the process, about 30 manuscripts will be produced, varying in length between 50 and 600 pages. In the next step, these manuscripts need careful editing so that the oral reports can be made available in a qualitatively appropriate way as written texts in Enlhet.

Knowing from experience that translating Enlhet reports into German, Spanish or English ties up a lot of resources over long periods of time, we want to concentrate on editing the reports in their original language in the coming years and making all our recordings accessible in Enlhet. Given the volume of these recordings, this process will likely take ten years.

Invitation. If this endeavour and these goals appeal to you, we would like to invite you to support our work financially. From 2000 to 2017, the work of Nengvaanemkeskama Nempayvaam Enlhet (NNE) was largely funded by Rainforest Norway, and between 2018 and 2020 also by the Interamerican Foundation. However, after the complete withdrawal of Rainforest Norway from Paraguay and changes to the goals of the US government after 2018, we have received no financial support since. We are hoping to secure new funding commitments from private donors and hopefully new funding partners; otherwise it will be difficult to fulfill the mandate of the elders and make their accounts available to their people.

If you would like to make a one-time or regular contribution, you are welcome to do so through:

In Canada

Andrés Pablo Salanova

Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC), 41 Rideau St, Ottawa ON K1N 5W8, Canada

Swift: CIBCCATT

Institution number, Canada: 010

CAD account: 00016-86-84235

USD account: 00016-93-45183

Intended purpose: Enlhet Project Paraguay

Martin Kalisch

IBAN: DE46 6945 0065 1150 0428 27

BIC: SOLADES1VSS

Intended purpose: Enlhet Project Paraguay

We would be happy to keep you informed about the progress of our work. Please contact us via nempayvaam@enlhet.org if you would like to receive our newsletter.